- Home

- Resources

- Topical Time

- Bonus Content: SS Kateria

Bonus Content

SS Karteria

originally published in Topical Time, January-February 2023

The article below was originally published in the January-February 2023 edition of Topical Time. Please enjoy the article in the text below or using the flip book version displayed to the right. This feature is adapted from the author’s book, The Art of Stamps: Messengers of History and the Character of Nations. More information about the author and the book is available at www.theotocatos.com.

|

The Story Behind the Stamps The SS Karteria – Legendary Greek War Ship by George Theotocatos Greece has been a maritime nation since its earliest times. The Greeks were skillful shipbuilders, seamen and navigators. Their warships were in a class of their own. While there are many nautical stories to tell, the SS Karteria stands particularly tall for the legacy she left behind.

|

The S/S Karteria was the first steam-driven warship in the world to engage in naval battles successfully and was a significant force in Greece’s War of Independence of 1821. She was the most modern warship in active service in 1826. In her short four years of duty in the Aegean Sea, she inflicted heavy damage on the enemy and helped the small Greek navy defeat a much more powerful force and finally gain independence. This is Karteria’s story and the legacy of her creator and captain, Frank Abney Hastings.

Built in the Brent Shipyards in England in 1826, Karteria displaced 233 tons and had an overall length of 159 feet. Her hull was constructed of wood and sheathed in copper, with five coal-fired steam engines, each rated at 42 horsepower. Steam from the boilers powered two paddles, each having a 12-foot diameter. The engines at full power could sustain a maximum speed of around seven knots (8 mph). She burned seven tons of coal per day through a 40-foot high stack. The ship was also equipped with four masts that allowed the crew to shift from engines to sails in favorable weather conditions.

The ship was created and constructed under the supervision of Captain Frank Abney Hastings (1794 - 1827), a British naval officer who also served as ship commander. Hastings was from an aristocratic English family and strongly supported the Greek Revolution. He was the son of a military man, General Sir Charles Hastings, who joined the Royal Navy as a volunteer on the sloop Neptune in Admiral Lord Nelson’s fleet. At the young age of 25, his royal navy career ended, however, due to conflict with his superior officer.

Captain Hastings was described by Lord Byron as “intelligent and scientific, of great courage and coolness as well as enterprise.” He was a dedicated Philhellene with a great love for Greece. For the remainder of his life, he played a vital role in the Greek War of Independence. He first arrived in Greece on April 3, 1822, volunteering his services and wealth for the Greek cause. He landed on the island of Hydra on a Swedish brig one year after the Greeks declared their independence from the Ottoman Turks after 400 years of occupation. Hastings participated in several battles on the side of the Greeks while at the same time formulating plans on how to upgrade the new Greek navy. He believed the only way Greece could achieve military superiority and win the war against the Turks was by using steam-driven warships. Hastings was concerned that threats from the newly invading expeditionary army of 30,000 Egyptians who had landed in Peloponnesus to assist the Turks under Ibrahim Pasha were serious. He concluded that the Egyptian expeditionary force and the Turkish troops could only be dealt with by improving Greek naval power, and by organizing the homeland forces and feuding Greek chiefs.

In the summer of 1823, Hastings sent a detailed proposal to Lord Byron. In it, he outlined his assessment of the ongoing conflict between the Turks and Greeks. He included a strategic plan of how the Greeks could achieve superiority over the Turks. His main idea for a successful war campaign was to build and promptly engage in the war theatre using a steam-propelled warship with superior speed and armament. Hastings pledged 10,000 British Pound Sterling of his own money on the condition that he would command the vessel. His letter also included operational details against the enemies’ fleet, outlining how to effectively utilize the ship’s superior maneuverability and firepower against the opposing navy. His innovative ideas must have sounded preposterous to men accustomed to traditional naval battles. The very notion of a paddle-driven steamer going around in circles alternately firing hot shells from one side of the ship and then turning quickly to fire from the other side would have been alien to the military people of that day.

In 1824, Lord Byron, at the request of the London Greek Committee, traveled to Greece. His arrival allowed Hastings to refine his war plans and present them to Byron for his support.

In 1824, after long delays and much hassle among politicians and military men, the Greek authorities agreed to purchase the first steamship, with six more to follow. The need was now urgent. They asked Hastings to return to England to oversee the purchase and construction of the new ship. By May 18, 1826, construction was completed, and to the great delight of Captain Hastings, the Karteria left the Thames Estuary on her sea trials. He personally selected the crew in preparation to sail from England to Greece. After successful trials, on May 23, she returned to berth in England to take final supplies. Three days later, the Karteria under the command of Captain Hastings, with a crew of 187 sailors and 17 officers, left England for Greece. To assist the war effort, Lord Byron’s friend and traveling companion, Dr. Bruno, also boarded the vessel to return to Greece.

Figure 2. This 1983 from Greece depicts the Karteria and her figurehead.

Figure 3. The other five stamps in the series with Karteria depict additional sailed

warships engaged in the 1821 war of independence against the Turks.

During this voyage, Hastings experienced many troubles with the engines, the crew, death on board, and the feeling that he lacked the support needed from the Greeks and their representatives in London. Luckily, the initial voyage to the Mediterranean was uneventful, with fair weather following. After they passed the Rock of Gibraltar, they had to rely on the engines for the first time as the favorable winds died down.

Unfortunately, two days later, one of the engines exploded. There was suspicion that the cause of the engine failure may have been sabotage. By the time they reached Sardinia, a second engine had broken down, and Hastings decided to anchor in the Bay of Cagliari to repair the damage. By August 1826, the two engines were fixed, and the remaining work was done at sea on the journey to Greece, which took another two weeks.

They finally arrived at Kythera in the South on Peloponnesus at a time when the war was not going very well for the Greeks. The important city of Mesolongi was in ruins (the stamp on the cover of the author’s book depicts the siege of the city), and Athens was in the hands of the Turks. The timely arrival of the new warship Karteria brought an air of optimism to the war effort. Her immediate contribution was precious, turning the tide of the war in favor of Greece and finally helping the country achieve independence.

In 1983 a stamp featuring the legendary ship showed an enlarged picture of its nautical figurehead of a bow woodcarvings known as “acroprora” or “acrostolia.” These carvings decorated Greek merchant and warships exteriors during the Greek revolution of 1821. The origin of these figureheads dates back to ancient times. They are rooted in superstition - the translation of “acroprora.” Greek tradition held that the figureheads were a protection against the dangers of waiting mermaids or other maritime demons.

The Hellenic Post Office’s 50d stamp of Karteria (Figure 2) was one of six stamps in a set issued in 1983. Only 800,000 stamps were printed in multicolored offset by Aspioti-Elka Graphic Arts ltd in Athens. The stamp is 27x40 mm and was produced in sheets of 50. The artist was P. Gravalos. The remaining five stamps (Figure 3) depict other sailed warships engaged in the 1821 war of independence against the Turks.

Here’s the historical account of the events at Kythera...

On the night of September 14, 1826, at full moon, the ship steamed up the gulf of Argos with her two paddles creating a dual wake and trailing a black cloud of smoke out of her 40-foot chimney. Despite political intrigue and infighting among Greek leadership and factions, along with Ibrahim’s continued assault on Greek forces, Hastings increased his determination to ready Karteria for action. His orders finally came to enter the war theater sailing from Egina to Salamina. He successfully guided the ship through the narrow straits and finally anchored off Phaleron. With his superior navigational skills and the ship’s firepower – her guns were much more sophisticated than previously seen in Greece – she bombarded the Turkish forces stationed on land, thereby helping relieve the siege of Athens. Karteria continued to seek, engage and destroy the enemy inflicting heavy damage to the Turkish ships and enemy ground forces. Her large caliber guns helped the Greek navy control the seas and shores, sinking many enemy ships and destroying enemy fortifications and troops on the Greek shorelines.

Karteria’s most famous battle occurred near the port of Itea in the gulf of Corinth. The naval battle lasted two days, from September 29 to 30, 1827. Although three other Greek sailships escorted her, she single-handedly engaged the combined Turkish and Egyptian fleet of nine warships and three Austrian transport ships, including the Admiral’s brig. Karteria destroyed seven enemy ships and took three Austrian ships as prizes. She also engaged and destroyed the enemy shore batteries used to protect the enemy armada.

In 1828, a second steamship arrived in Greece: the Epicheirisis. She was smaller than Karteria, and its engines never performed to Karteria’s standards. The captain of Epicheirisis was a professional seaman whose real name was Downing but who went under the alias Kirkwood. Without the perseverance and commitment of Captain Hastings and owing to the inferior seaworthiness of the ship, Epicheirisis never achieved any notable success in the war.

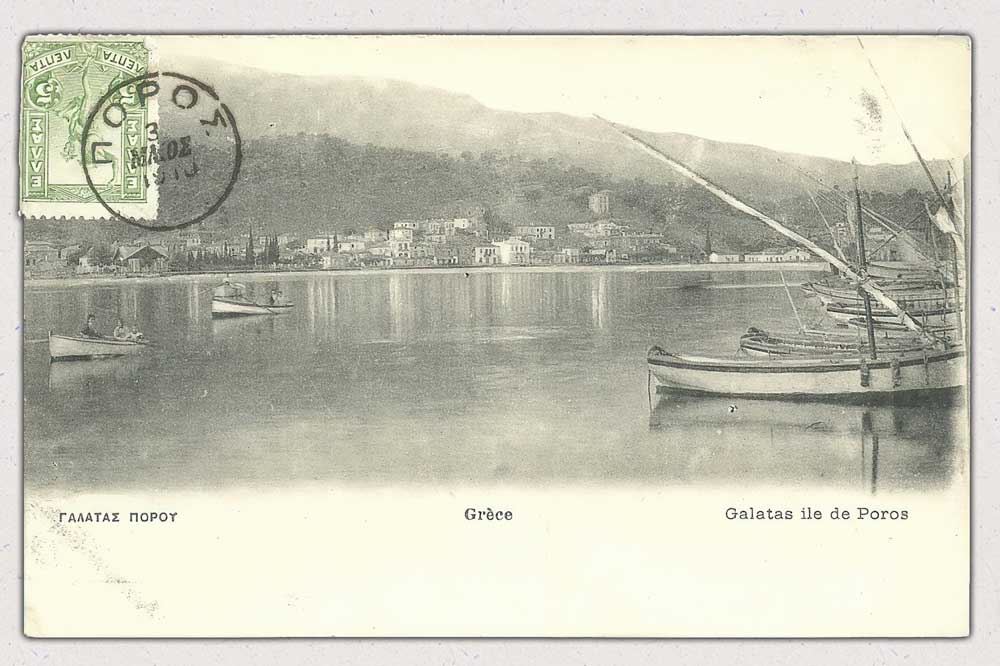

Figure 4. A postcard showing the Island of Portos where Captain Frank Abney Hastings was buried.

On May 1, 1987, while aboard the ship bombarding enemy land positions, Hastings took a bullet in his left hand. As his condition worsened, he was transferred to a hospital, but without the ability to amputate his arm, they could not save his life. The man who inspired the design and construction of the most successful warship in battle died in Greece on June 1, 1828. His remains were transported to the Island of Poros (Figure 4) a year later—fittingly so, aboard the Karteria and escorted by the steamships Epicheirisis and Hermes. He was buried with full honors. Hundreds of people turned out for the funeral procession, including ministers of the Greek government, representatives of other nations, and ordinary seamen. In doing so, they honored all the men who died in defense of Greece. Captain Frank Abney Hastings had indeed become part of history.

The SS Karteria was decommissioned in 1831.