- Home

- Resources

- Exhibiting

- The Writeup

Philatelic Exhibiting 101: The Writeup

by Robert R. Henak, originally published in Topical Time

Beyond sloppy presentation, few things frustrate a judge more upon initially viewing an exhibit than page after page with huge blocks of text, knowing that there likely are pearls of wisdom buried in those pages that we simply do not have the time to find. The ideas discussed here generally could apply to any kind of exhibit, not just those that are thematic or thematically organized. And, again, there are no “rules.” These are simply one exhibitor/judge’s thoughts that he has found to be helpful. WHY? The first thing to ask yourself when considering the write-up for your exhibit is “Why?” Why do we even write up the exhibit? Why not just let the material do the talking and carry the story along? These may seem to like silly questions, but it is always both important and helpful for the exhibitor to ask himself or herself why each particular sentence, paragraph or clause of write-up is included in the exhibit. Is it necessary to move the story along, or is it just some irrelevant information that the exhibitor found interesting? Does each particular part of the write-up help tell the story, or do some parts just bog the reader down? Worse, does the added information distract the reader (and here I mean the judges as well as the general public) from what information you most want to get across? WHO?

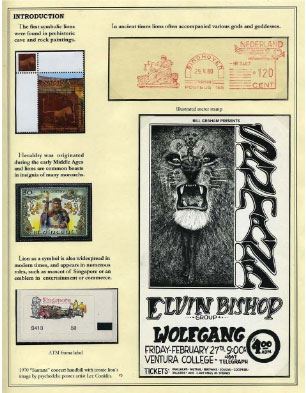

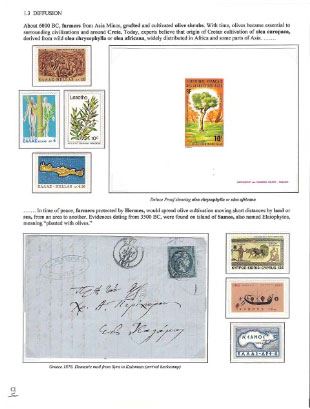

If you are exhibiting primarily for the public, or for some particular subset of the general public, such as children, your write-up may emphasize things differently than if you are focused on impressing the judges. For instance, the general public and children likely will be more interested in the thematic aspects of your write-up than the “philatelic knowledge” side, and you likely would want to use less technical vocabulary. The write-up for the general public also likely would require “filling in the holes” in terms of background information that an exhibit targeted at judges or other more experienced philatelists would not require. On the other hand, a write-up targeting the judges likely would focus more on balancing the thematic with the “philatelic” write-up necessary to show your philatelic knowledge. Even further along the scale, the write-up for an exhibit focused more on fellow experts in your chosen field than on your usual generalist philatelic judge could incorporate even more technical vocabulary while assuming a greater level of basic knowledge. WHAT? As with most types of exhibits, a thematic exhibit is expected to tell a story. With a thematic exhibit, however, the story line is about a non-philatelic subject, be that Lions, Backyard Chickens or a comparison of America’s “Gilded Age” with France’s La Belle Époque. Therefore, unlike for most other types of exhibits, the write-up for a thematic exhibit must serve two purposes. While the write-up for a traditional or postal history exhibit will be primarily – if not exclusively – “philatelic,” the write-up for a thematic exhibit must help further the thematic storyline as well. The secret of success is to both tell the thematic story and display your philatelic knowledge without overwhelming the viewer with prose. One may ask why even bother with a philatelic write-up in a thematic exhibit? The answer, of course, depends once again on the chosen audience. As previously noted, if the exhibit is targeted at the general public or children and the exhibitor does not care about medal levels, then philatelic details demonstrating the exhibitor’s philatelic knowledge are not that necessary – if at all. Under those circumstances, including write-up showing philatelic knowledge may actually distract from what the exhibitor seeks to achieve. However, if the exhibitor wants to earn a high medal level or award, then a write-up, well-balanced between the thematic storyline and demonstrating philatelic knowledge is crucial. Philatelic knowledge in a thematic exhibit is shown in part by the exhibitor’s use of a wide variety of appropriate philatelic “elements” that we discussed in earlier articles. With a few caveats, however, it generally is helpful to identify them. Thus, if you show something unusual, such as a semipostal stamp, an overprinted stamp, a pictorial cancel, a trial color proof or an aerogram, identify it as such.

However, do not bother identifying every regular or commemorative stamp. Likewise, do not include Scott numbers or similar catalog numbers. Such readily available information does not help your “philatelic knowledge” score and just clutters the pages. WHERE? While there are no requirements for where on the page to place your thematic or philatelic write-up, there are a few suggestions of things that I have found to be helpful in reviewing someone’s exhibit. For instance, the philatelic write-up for a particular item should be immediately under – or next to – that item. Don’t make the viewer search to find the write-up describing an item. Similarly, the thematic write-up should be near the philatelic material used to illustrate the point made in that write-up. That is, if the thematic write-up is discussing the evolution of the horse, it should be near the stamps, or whatever, illustrating that point so the connection is obvious. There is no requirement that the thematic write-up be at the top of the page, or that the entire thematic write-up for a page remain in one big clump. Experiment with different layouts and see which one works best for you. HOW? When writing up your exhibit, keep in mind that it is a philatelic exhibit. That may seem obvious, but many exhibitors get so excited about their material and the research they have done that they want to include everything they can in the exhibit. That may be appropriate somewhere else, but not in a philatelic exhibit. I find it helpful to keep in mind that there are a number of different formats for presenting information, with the amount of information provided in the write-up depending on the amount of time the viewer is expected to be able to spend. Thus, a PowerPoint or a museum exhibit generally provides less information than a philatelic exhibit, while a magazine article or a book on the subject will provide much more detailed information. Remember that neither judges nor members of the public generally have the time nor the attention span to stand in the aisle at a stamp show to read page after page of dense text. Keep your write-up brief! Keep in mind that your write-ups need not be complete sentences as long as you get the information across. Since we all tend to be wedded to our own eloquence, it may be helpful when confronted with huge blocks of text on your exhibit pages to have someone else edit them with a view toward cutting the excess. In my law firm, where I regularly tend to bump up against page limits, we refer to this as “slash-and-burn” editing. Of course, since it is important to have philatelic material illustrating each point in the thematic text, big blocks of text suggests that illustrating material is missing. If all the text in that block is necessary, then split it up and team it with appropriate material. On a more general point, one way to think about the write-up that is especially helpful in a thematic exhibit is to divide the write-up into three different levels or types to reflect the three types of information generally included in an exhibit: The first level is the basic thematic storyline. The second level is thematic information that may be interesting but not critically important to understanding the main story. The third level is philatelic information that is unrelated to the thematic story. When the exhibitor consistently differentiates these three types of write-up throughout the exhibit, as by using different fonts (or even, as some exhibitors do, different colors of type), a viewer is able to immediately identify what he or she is most interested in on the page. If someone is interested only in the main thematic storyline, he or she can limit themselves to that without getting bogged down in other information that is less interesting to them. While the exhibitor can experiment with this, the easiest and least distracting way to create the three-level write-up is to use different fonts, perhaps a larger serif font for the main storyline, a smaller version of the same font in italics for the second level, and perhaps a bold sans serif font that is smaller yet for the philatelic information. Jerry Miller, an exhibitor from Chicago, first introduced me to this method, although he uses different colored type for the three levels. I have used it in my own exhibits since. One final suggestion that tends to be especially helpful with the main storyline in thematic write-ups is to extract a copy of the thematic write-up from the exhibit pages into a single document. Then read through it without the distraction of the philatelic write-up or material to see how it flows and to identify any obvious holes in the story. You might also be able to identify any typos more easily without the distractions of what else is on the exhibit pages. As always, there are a number of ways to learn about what works in exhibit write-ups: trial and error to see what works best for you, viewing exhibits at shows (when it is safe to have shows again) and listening to the judges’ comments, or just looking at a number of exhibits, such as those online exhibits I identified in my last column. |

Having taken a slight detour last issue to discuss exhibiting during the pandemic, it is time now to get back to the nitty-gritty of exhibiting. We previously discussed the title page, the plan, the nuts and bolts of paper and page protectors, as well as the types of philatelic material that are consistent with traditional conventions of thematic exhibiting. This issue, we discuss the write-up.

Having taken a slight detour last issue to discuss exhibiting during the pandemic, it is time now to get back to the nitty-gritty of exhibiting. We previously discussed the title page, the plan, the nuts and bolts of paper and page protectors, as well as the types of philatelic material that are consistent with traditional conventions of thematic exhibiting. This issue, we discuss the write-up. As I discussed quite a while ago, identifying your chosen audience should influence just about everything about your exhibit, including how you approach your write-up. Your target audience should impact not only the information you choose to include in the exhibit, but also your word choice and perhaps even your choice and size of font.

As I discussed quite a while ago, identifying your chosen audience should influence just about everything about your exhibit, including how you approach your write-up. Your target audience should impact not only the information you choose to include in the exhibit, but also your word choice and perhaps even your choice and size of font. If the item is rare and you can put a number on it (such as, “one of two printed,” or “one of 10 recorded”), then do so. However, note that there is a difference between “1 of X recorded” and “1 of X known.” The former generally refers to an actual survey (which should be identified in the synopsis), while the latter refers to the exhibitor’s non-formalized knowledge from experience (the extent of which similarly should be identified in the synopsis).

If the item is rare and you can put a number on it (such as, “one of two printed,” or “one of 10 recorded”), then do so. However, note that there is a difference between “1 of X recorded” and “1 of X known.” The former generally refers to an actual survey (which should be identified in the synopsis), while the latter refers to the exhibitor’s non-formalized knowledge from experience (the extent of which similarly should be identified in the synopsis).